And I probably had five or six grams left. In less than an hour, I’d made over $1,000. "I was in Wheatland less than an hour and one guy had sold it all for me.

"I couldn’t believe the first time I had an ounce of crank," Ory says. It’s easy after that, especially for a clean-cut white man obeying all the traffic laws. I went and got more the same day, and it just started." So I came back the next day with maybe six or seven hundred bucks, bought a half ounce. "But I’m thinking, Wow, I need to make this 450 bucks back. "Maybe he was shocked at that point that I’d come in just like that," Ory says now. "I came to buy, and he was going to get it here." "He came in and went out the bathroom window with your drugs about three hours ago." He got on the phone, spoke in Spanish, which Ory doesn’t understand, then hung up. The Mexican eyeballed Ory, checked up and down the block, trying to figure out if he’d been sent by the cops or was just an idiot.

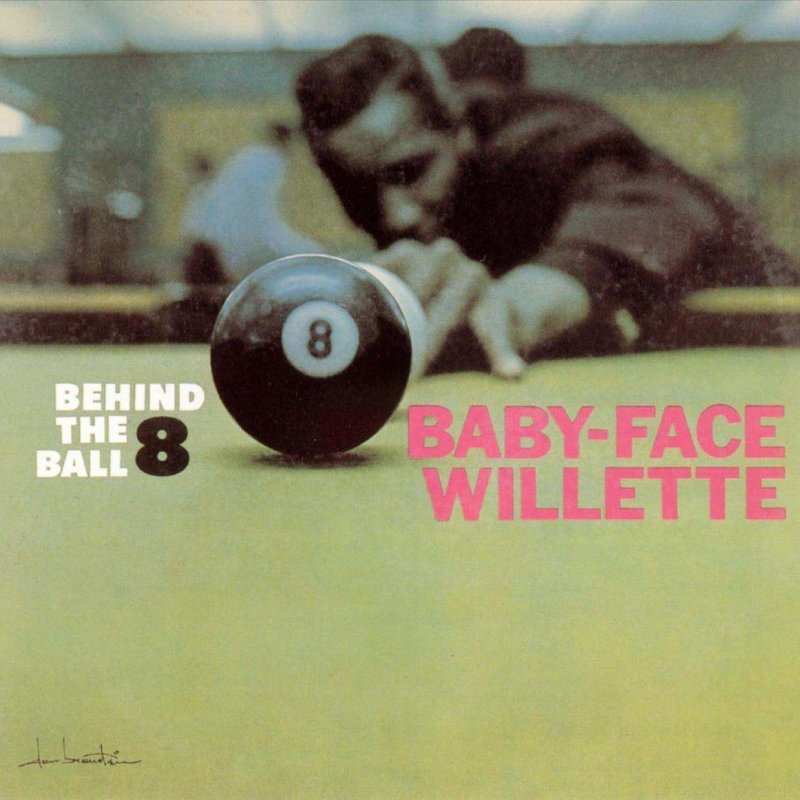

So I go and I sell a gram to this guy and another gram to this guy, and now I’ve got a gram and a half for free." He pauses for a beat. Well, I know people who would want grams. The friend Ory bought from told him that an eight ball-an eighth of an ounce, three and a half grams-sold for $200 in Scottsbluff, a city of 15,000 on the other side of the Nebraska line.

#HEROIN 8 BALL PRICE HOW TO#

Step two to becoming a small-town dealer: Figure out how to make the economics work. By the end of February 1997, he was snorting two, maybe three grams a day, which at $100 a gram, ballpark, is unsustainable for a kid who doesn’t want to start breaking into cars and houses. From then on, I walked."īut for a brain wired a certain way-like Ory’s, apparently-crank is notoriously addictive. "I hadn’t put any weight on my foot, and I was able to put down my crutches that night and walk. "It was the first time I’d walked since the wreck," he says. Some guy had some crank, a common precursor to proper methamphetamine that was brewed by rednecks and bikers. Six months later, when Ory was still hobbling around on crutches and swallowing Vicodin, he went to a party. This is disturbingly common among both buyers and suppliers. Step one to becoming a small-town drug dealer: Develop a medically prescribed, and thus completely legal, addiction to opiates. When he ran out of pills, he always got some more, and it didn’t seem to matter how often he ran out. A judge gave him two years’ probation for misdemeanor DUI, and a doctor gave him Vicodin for everything else. His Suburban hit a bridge railing at highway speed, crushed the front end, broke Ory’s nose and jaw and collarbone, bruised a lung and his liver, shattered his right ankle. He drove home drunk and fell asleep on a dirt road about a mile from home. One Saturday in the summer of 1996, when Ory was 19 years old, he spent the day drinking beer out at Springer Reservoir, a lake south of Torrington. Ory thought, for a while, that he might want to be a dentist, like his best friend’s father. He turned it down because he didn’t want to be a musician. He hunted and fished, and he wrestled and played baseball for his school, mastered the piano, and was so good with a trombone-marching band, jazz band-that a college back east offered him a scholarship. He was a popular kid, amiable and bright, president of his class in grade school, student-body president his junior year in high school. Ory, rather, is an industrious and entrepreneurial man of 37 who was born and raised in Torrington, a smudge of a village near the Nebraska state line, where his father was the town veterinarian.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)